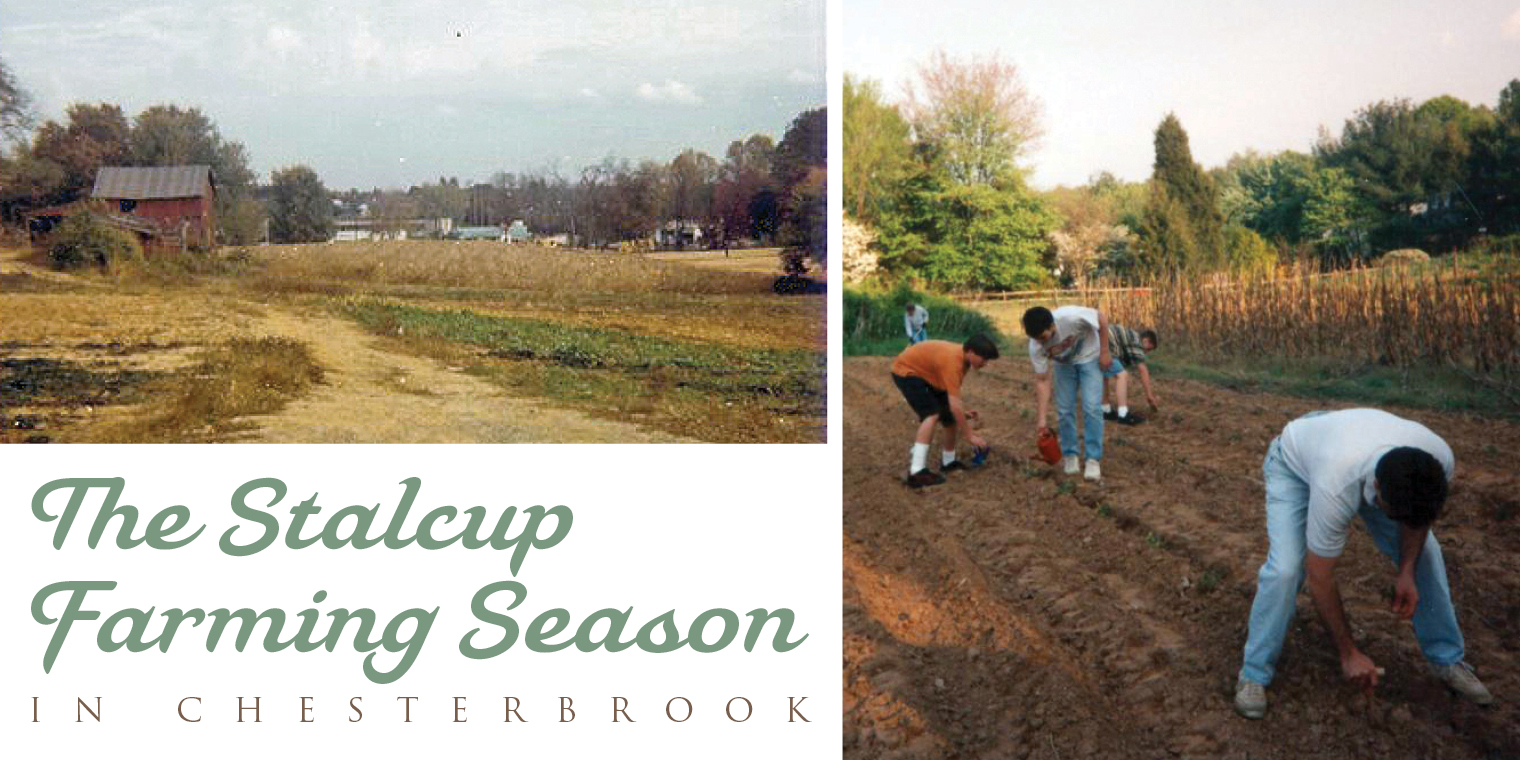

After the close of World War II, the rural, agrarian character of Fairfax County began to develop a suburban atmosphere, spurred on by the many government employees who remained in the greater Washington metropolitan area. Farms and fields disappeared as they were replaced with residential housing and a few government buildings. The dramatic change for the McLean area came when the CIA decided to relocate to Langley. By the time the agency opened in 1963, McLean was no longer a farming community. Suburbia had arrived. However, there was one holdout in the community of Chesterbrook. This was William Stalcup, whose family continued farming the land until the beginning of the twenty-first century. His residence consisted of five acres on Park Road. Not only did the family farm their land, but they farmed other small parcels scattered throughout Chesterbrook.

Few realize that the rhythm of farming has an annual cycle. The farming season for the Stalcup family started each year when it was time to “work-up” the ground for planting such things as potatoes, peas, corn, tomatoes, squash, and strawberries. In the spring it was generally a challenge to get the soil in condition for planting because the ground was wet. It was usually mid-March before the Virginia clay was dry enough to break apart without becoming cloddy. More often than not, work needed to be done before preparing the ground. If there was a fairly good-sized late snow, the Stalcup children had the task of building a large snow pile that would last well into the spring. If the shipment of strawberry plants arrived before the ground was ready, the snow pile would be used to keep the plants cool until the soil was ready for planting. Once the ground was prepared, a month or so would be spent disking the land and then planting the various crops. The Stalcups did not plant everything at one time. They spaced their plantings apart so that harvesting was continuous and spread over the greatest time period possible. For instance, corn was planted every week or so in order to have a half-acre patch getting ripe about every week.

The first of the tomatoes were planted in late April in order to start picking as early as possible. The family claimed that early tomatoes were much more valuable than ones picked in August when the market was glutted. A late spring frost was always a problem. It was particularly dangerous to newly planted tomato plants as well as blooming strawberries. A frost would often come when the early tomatoes were small. This was around the time strawberries were in bloom, which was about a month before picking. If the blooms froze, the strawberries died. Therefore, whenever frost was predicted, or even a possible frost, in the outlying suburbs, everyone would frantically try to prevent damage to the tomatoes and strawberries. Old newspapers were used to make tents that covered the plants. The papers were formed into a tent-like shape and a person placed one over each plant while putting dirt or rocks on the corners to hold it in place. These tents would give the fragile plants some level of protection. One year the Stalcups learned about a method used by Japanese farmers. To prevent frost damage, the young plants or blossoms would be given a good water dousing before the sun hit them. At first, the Stalcups felt guilty when they stopped tenting because the new watering method was so much easier. But the Japanese method really did work and made their job a good deal easier.

Around Memorial Day the strawberries began to ripen. This might vary by a week or so depending on how warm the spring had been. This was a time when any and every person who lived on Park Road was recruited to help pick the berries. The strawberry season was about two-and-a-half to three weeks long. During that time, the workers would gather together early in the morning and wait for enough light to pick. Each person would be assigned a row. The criterion for the assignments probably had to do with picking ability.

Besides the William Stalcup family, there was quite a bit of neighborly help. The most consistent helpers were Peggy Stalcup Byers and her children Margaret, Nancy, Alton and Elizabeth. However, there were many other regulars throughout the years that included Harry and Dotty Sells. William’s son Sam suggests that Chesterbrook lore recalls that “Dotty was extremely competitive at picking and she constantly tried to be the best. Occasionally she thought the berries were riper on other people’s rows and would fail to observe the strawberry row territorial boundary rules. Dotty was a fast picker, but when she got tired or too hot, both she, and her husband Harry, would violate the ‘No Sitting’ rules, as often witnessed by their berry stained rears.”

It took about an hour and forty five minutes to pick the berries each morning. This back-breaking job started as soon as there was enough light to know if the strawberries were ripe in color. This was early in the picking season when it was chilly and the berry patch was generally wet from the morning dew. As one picked, his hands would get very cold, and often numb. Early in the season everyone’s back and legs would get extremely sore from bending over and straddling the rows. But this was the only way to get any speed; and speed was everything. A person’s stature as a farmer was in large part determined by the number of quarts he picked in about an hour. Fortunately, the soreness went away after a few days. When walking down between the rows, a picker had to be careful not to knock over the full quarts. The major offenders were the dogs. During peak season, between 100 and 200 quarts of strawberries would be picked each morning. According to Sam, “It was a beautiful site to see crates of bright red berries. It made all the planting, hoeing, weeding, bending and spreading straw, worthwhile.”

I can remember very clearly that Big Daddy would assign me an end row. It was always shorter than the rest of the rows, and always “scimpier’. Big Daddy would tell me, “As soon as you can beat me picking a box of berries, you can quit.”. So, he would pick along side of me, and I would keep tabs on how he was doing, and I would see that not only was I apparently keeping up with him, I might even be a little ahead of him. Then, he would look sideways at me and grin and suddenly dump a huge handful of berries into his basket and totally blow me away. He had been holding out on me!!!

Also, remember that you would not want to use the quart baskets more than once because the berries would leave stains. Also, Mom would not let people sort through the crate and pick out their “reserved quarts” and they would never be allowed to lift up the divider to look at the bottom layer before the top ones were sold.

In the early 1960s, the Stalcups started planting tomatoes in large numbers. In the beginning, the plants would just lie in the dirt, causing them to get muddy and the tomatoes generally to be of poor quality. To counteract this, they began staking the plants. This kept the tomatoes suspended and clean, but it involved an incredible amount of work. A person would put a stake next to each plant and train the plants by tying them to the stake, using strips of cloth. It was tedious, had to be done very regularly, and was time consuming.

Eventually, they found a cheaper, easier way to solve the problem of the time-consuming method of staking the plants. Twenty or 30 bales of straw were purchased for each tomato patch. When the plants were large enough to start flopping over, they were given one last hoeing, followed by spreading straw over the entire patch. This was done one plant at a time. This mulching served three purposes: it kept the weeds in control (assuming straw was used, not hay); it held the moisture in the ground during the sizzling weeks of July and August; and it kept the tomatoes clean. This was hard, sweltering work, particularly because it was done in the middle of the day: the morning hours were for picking. It was also grueling because the mulcher had to bend over in the hot humid tomato patch. Each quarter-acre patch was typically 500 plants. Sam claimed that “A finished planted patch was a beautiful sight. The rich green of the tomato plants would contrast with the light gold color of the freshly spread straw.”

Farming in Chesterbrook was eclectic in nature. There were three schools of thought for dirt farming. Primarily, there was the William Stalcup method. This approach came from a long line of Stalcup farmers and was the baseline for the Stalcup family. Another approach came from the grand old farmer himself, John Beall. His farm was located along Kirby Road at Linway Terrace, not too far from the Stalcup place. John was a farmer’s farmer. He was easily as at-home with his cows, as he was with people. He dressed, looked, thought, and talked like a farmer. He was of the old school. Lastly, there was Tony Newcomb who received his degree in economics from Oberlin College and represented the new, scientific and altruistic school of farming. The Beall and Newcomb opposing viewpoints created conflict in the Stalcup’s baseline methodology.

Even in terminology this conflict was felt. The old school said pull the corn and new school said pick the corn. Anyone who said pick was pitied as being deprived of the fullness of tradition. The old school pulled corn a hand at a time. A hand consisted of 15 ears (never say cobs or corns). When the corn puller had 15 ears balanced in a cluster in the crook of his left arm, he would yell, “Here!” A bag boy would rush over and receive the hand into his burlap bag. The old school gathered, moved, and stored sweet corn in burlap gunny sacks. The bag boy would hold the top of the bag at two points, a third of the way around the top, and the puller would grab the third point with his free hand. This formed an equilateral triangle opening in top of the bag and the puller would dump in the hand. The productivity of a morning was measured in terms of the number of bags filled. Each bag held 60 ears, or four hands. The bag boy would hold a bag until it had four hands; it was his job to count the hands. Sometimes he would forget how many hands were in the bag. To avoid selling a bag without the proper number of hands, he would mark the bag by breaking off a stalk and putting it in the top. When the bag was full the bag boy would carry the bag to the row where the corn was picked up and hurry back to address the next “Here!” When the pulling was finished for the morning, a tractor and trailer would knock down the pickup row and everyone would throw the bags onto the trailer. In later years, bushel baskets were used to hold a bag and the puller carried it to the pickup row.

In the early to mid-1950s, there was only one kind of sweet corn grown in Chesterbrook: Golden Bantam. When the Stalcups became acquainted with Newcomb, they learned about many hybrid varieties. Hybrids were better in terms of taste because they had a higher sugar content making them much sweeter. However, more importantly, they were better in terms of productivity. The two main yellow corn hybrids were Gold Cup and Seneca Chief. Gold Cup was the farmer’s choice because it was easier to pick (pull). It snaps off the stalk more easily and produces more ears to the stalk. Also, the ears were nicer-looking. Seneca on the other hand has higher sugar content. Gold Cup was starting to win out over Seneca in Chesterbrook when Silver Queen, a white corn, came on the scene. Eventually, Silver Queen was the only corn the Stalcups grew because that was what the public wanted.

The old school insisted that it was necessary to sucker corn. Suckering was the process of walking up and down the rows of corn one at a time and yanking the side shoots (the suckers) off of each stalk that had them. The thinking was that these shoots would suck the strength from the main stalk. This again was hard work in the hot and humid summer. The new school claimed that suckering wasn’t necessary and, in fact, was traumatic to the main stalk. Farmers loved the new school of thought when it came to suckering, but it was hard for the old timers to give up.

The William Stalcup family sold their produce at a stand in front of their house. Their produce was also sold to William’s brother, Sam, who operated a stand on Saturdays at the K Street Market in the District, and, who in later years, ran a seven-day-a-week stand on Old Dominion Drive adjacent to the Chesterbrook Shopping Center. Payday was Saturday. This gave the workers a strong sense of financial accomplishment, and after the Sunday respite, they were ready to work the fields again come Monday.